The Tragic Life of Horatio Higbee, London Artist

Horatio Higbee was born 12 April, 18371 in Radcliff, London, England, to George Robert Higbee and Jane Kirby. Though no longer in existence, Radcliff was once a hamlet lying near the north bank of the River Thames between the districts of Shadwell and Limehouse. Today, this area is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, and is located just to the south of Stepney.

In this same year, Charles Dickens wrote of London; “Eleven o’clock, and a new set of people fill the streets. The goods in the shop-windows are invitingly arranged; the shopmen in their white neckerchiefs and spruce coats, look as it they couldn’t clean a window if their lives depended on it; the carts have disappeared from Covent-garden; the waggoners have returned, and the costermongers repaired to their ordinary ‘beats’ in the suburbs; clerks are at their offices, and gigs, cabs, omnibuses, and saddle-horses, are conveying their masters to the same destination. The streets are thronged with a vast concourse of people, gay and shabby, rich and poor, idle and industrious; and we come to the heat, bustle, and activity of NOON.”.

This was Horatio’s London, a bustling metropolis with masses of humanity of every thinkable variety. Young and old, healthy and infirm, industrious and lazy, wealthy and poor. Above all, poor, and growing by leaps and bounds. London’s rapid growth during the 19th Century was unprecedented. In 1800, London’s population was about 1,000,000, and reached nearly 4,500,000 by the 1880’s. Much of that growth can be attributed to the advent of the railroad coming to London. Starting in the late 1830s, competing railway companies pushed into London as far as they could, displacing the masses of poor, and then building their great train terminals. This created a ring of railway stations that are familiar names today: London Bridge Station (1836), Euston Station (1837), and Paddington Station (1838).

19th century London was also a city of great poverty, where millions lived in overcrowded and unsanitary slums. The life of London’s poor was graphically immortalized in the novels of Charles Dickens. Sketches by Boz, Bleak House, and Oliver Twist. We all have a sense of what life was likely like for little Horatio and his family.

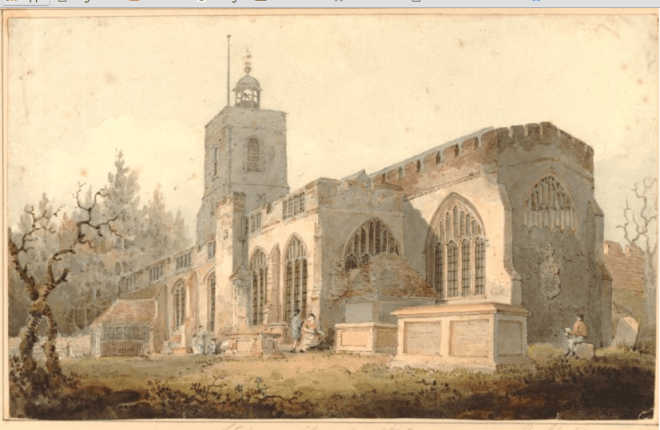

Horatio was the fifth child born to George and Jane. At the time of his birth, Horatio’s father, George, was a Mariner1. A Mariner at the time could have been a sailor, a merchant mariner, a fisherman or any number of other sea-and-ship-related professions. Horatio’s siblings included Mary Ann (born in 1829), possibly George Porter (born in 1830), Jane (born in 1831), and Emma (born in 1835). Horatio was christened 1 October 18372 in the Anglican Church at St. Dunstan, in the district of Stepney (Middlesex, England). St Dunstan’s has a history dating back to the 10th Century, though the building that Horatio would have known in 1837 was much newer, having been built in the 16th Century.

With a few upgrades since, that building still stands today. St Dunstan’s is surrounded by nearly seven acres of grounds and cemetery. The church itself has a long history and tradition of association with the sea. Many mariners and sailors are buried there. It was once known as the “Church of the Sea”. Perhaps that is the association it held for George Higbee and his family. This rendering is circa 1804.

The exact place of residence at the time of his birth is not known, but by the time Horatio was 4, the 1841 census notes that he and his mother were living on Diamond Row in Stepney3. Diamond Row no longer exists, but is known today as Redmans Road in Stepney4.

Horatio’s father George was not listed as residing at home in 1841. Perhaps as a Mariner, he was off to sea; however, it is possible he had already died by this time. His mother Jane’s occupation was listed in the census as being a Dress Maker.

By the time Horatio is 14 in 1851, he and his mother Jane, and his 16-year-old sister, Emma, are living as lodgers in the home of Mary Lethbridge5. Mary has a grown son, Richard, and a grown daughter, Frances, living in the home. Mary, Richard, Frances and Jane are noted as being widows and widower. Also living in the home is an older couple, John and Sarah Gall. The Lethbridge home is at number 24 Redmans Road, Stepney. The Redlands Primary School now stands on this spot where the Higbee family once lived.

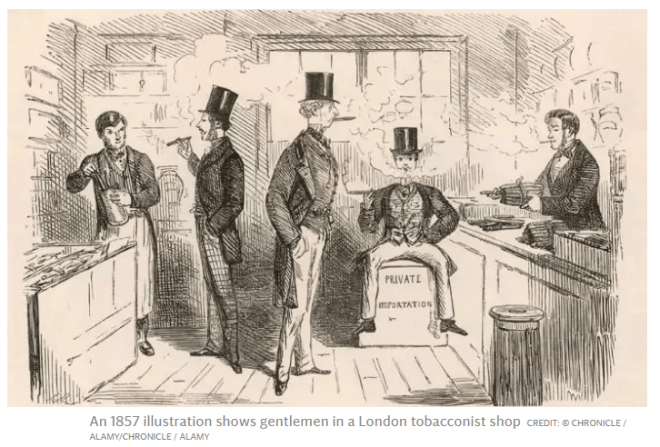

By 1856, young Horatio is working as a Tobacconist at 2 Wentworth Place, in the Mile End Old Town district6. He is listed in the City Directory of that year. While smoking in England had a long history, dating back to the sixteenth century, tobacco had been primarily smoked in pipes. Added to this over the years was both snuff and cigars. By the mid-nineteenth century, hand-rolled cigarettes, which had long been popular in continental Europe and the Middle East, were introduced to British soldiers during the Crimean War (1853-1856). It is likely that Horatio found himself making and selling a combination of the lot. With Horatio’s name being the only name mentioned in the City Directory at this tobacco shop location on Wentworth, it begs the question: is he employee, manager or owner?

On the 24th of April, 1858, at 21 years old, Horatio married Eliza James in the parish church, St. John of Jerusalem, in South Hackney. The church was fairly new in Horatio’s and Eliza’s time, having only been consecrated in 1848.

The original stone spire was damaged during the WWII and replaced by the current copper clad wooden structure. Its nave is 60 feet in height and the spire 187 feet. At the time of their marriage, the record indicates that both Horatio and Eliza were residing in South Hackney. Horatio’s father is again noted as a Mariner, while Eliza’s father, John, is noted as an Iron Foundry worker. No mention is made in the record as to whether George Higbee is deceased or living (though presumed dead from Jane’s “widow” reference earlier), but John James, Eliza’s father, is a witness to the marriage. While Horatio’s occupation in 1856 was as a Tobacconist, his marriage record in 1858 lists rank or profession as “Artist”. I find that very intriguing and wonder what type of artist he was.

1858 was a notable year for London, it was called the year of the “Big Stink”. For years, with the growing population of London fast outpacing the limited infrastructure to handle an ever-increasing volume of human waste, the River Thames had become the unfortunate but logical repository of that waste. Though London did have the beginnings of a sewer system, it was significantly underdeveloped. Many cellars had cesspools underneath their floorboards. With these cesspools overrunning, the London government decided to dump the waste into the river. The banks and depths of the river were becoming polluted beyond imagination, and the smells that hung over the city were stifling. This was a problem that impacted even the least sensitive noses of the wealthy, the middle class and the poor alike. It was also becoming much more clear, scientifically, that this waste problem was partly responsible for the many outbreaks of cholera that London had seen in the prior few years. By the summer of 1858, with summer temperatures at an unseasonable high, the problem became simply unbearable. Fortunately for the poor, the impact on the wealthy was so significant that they finally decided they needed to do something about the problem. An editorial in The Times of London on June 18th, 1858, reads:

What a pity it is that the thermometer fell ten degrees yesterday. Parliament was all but compelled to legislate upon the great London nuisance by the force of sheer stench. The intense heat had driven our legislators from those portions of their buildings which overlook the river. A few members, bent upon investigating the matter to its very depth, ventured into the library, but they were instantaneously driven to retreat, each man with a handkerchief to his nose. We are heartily glad of it. (GSOL, p. 71)

The public outcry finally prompted action from local and national administrators who had been considering possible solutions for the problem, including a series of sewers that would move the refuse far beyond the metropolitan area where it could be better handled. This historical event likely impacted the lives of Horatio and Eliza as well.

At the time of their marriage, Eliza was apparently already pregnant, as less than six weeks later, on June 8th, 1858, a son, Algernon Horatio Skingle Higbee, was born to Horatio and Eliza. A month after he was born, Algernon was christened on July 4th in the same church as his father, St. Dunstan’s in Stepney. Algernon’s christening record notes that their home address was number 65 King Street. King Street is no longer in existence, but was once where Christian Street now sits in Stepney7. This rendering is of King Street in 1886, slightly later than when Horatio and Eliza would have lived there.

It is just after Algernon’s birth that tragedy strikes the life of Horatio. The death index of 1858 indicates that Eliza James Higbee died in June. We do not have her death record so we do not have the details of her untimely death. However, we may surmise that perhaps she died in childbirth. Historical accounts also indicate that London experienced a significant Cholera outbreak in the summer of 1858, so was Eliza perhaps a victim of Cholera? One can only imagine how that tragic death might have impacted Horatio and the newborn Algernon. What would become of Algernon? What would Horatio do? For six months Horatio apparently struggled deeply with the loss of his wife. Several records seem to hint that Algernon may have been sent to live with other family members8. Horatio moved in with his widowed mother, Jane, likely near where he worked. The depth of Horatio’s despair was highlighted in a tragic news story from the London Morning News, dated December 24, 1858:

Extraordinary suicide. Yesterday afternoon Mr. W. Baker, the coroner, held an inquest at the Fountain Tavern Stracey-Street, Stepney, on view of the body of Horatio Higbee, age 22 years, who committed self-destruction by swallowing a quantity of prussic acid, under the following circumstances: Jane Higbee, of No. 69 King Street, near the Thames police court, said the deceased was her son, and lately he had been lodging with her. He was formerly in business at Mile-end, but through the death of his wife and other afflictions his mind had been unsettled. Deceased would frequently sit for hours in a low in melancholy mood, and was evidently disturbed in his mind. On Saturday last deceased came home from his occupation, and seemed rather dull, but made no complaint to witness. He partook of supper, and about 11 o’clock he retired to his sleeping apartment, and witness saw no more of him until the following morning about 9 o’clock, when she went to his room to call him to breakfast, but she could not gain admission, nor obtain any answer. Witness called assistance, when the deceased was found lying on the bed with his head hanging down towards the floor, and he seemed to be quite insensible. There was a little vomit upon the carpet, as if the deceased had been sick, and witness found a teacup containing a portion of liquid. Medical aid was sent for, and Dr. Corner soon arrived, and pronounced life extinct. There was no writing or anything found in the room to account for the act. Dr. Corner, of Ireland Road, near Mile-end Road, Stepney, said that when he reached the house and examined the body he had been dead several hours – most probably from the previous night. There was an appearance of the deceased having died from poison, and upon making an analysis of the liquid found in the cup, witness ascertained by tests that it contained cyanide of potassium or prussic acid, a deadly poison, used in photography. Other evidence having been taken, the coroner remarked on the case, after which the jury returned a verdict the temporary insanity.

This was the deeply tragic and heartbreaking ending of the life of a newlywed and a young father. Perhaps the challenges of life were just too much for the sensitive heart of this aspiring artist. Temporary insanity? Who can say. But certainly he died of a broken heart.

Horatio’s own signature on his marriage record

Footnotes:

1London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1906 , Tower Hamlets St Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney 1837

2 England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975

3 file:HIGBEE Jane Kirby 1841 Stepney Middlesex England census no George Robert in the home son Horatio.jpg

4 http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/rd/744bf61a-564a-48c4-87ba-a16a17495386

5 1851 census

6U.K., City and County Directories, 1600s-1900s

7 http://www.maps.thehunthouse.com/Streets/New_to_Old_Abolished_London_Street_Names.htm

8Census for 1861: HIGBEE Algernon Horatio Skingle 1861 Spitalfields Whitechapel London England census 2 years old living with half aunt & uncle Robinson HIGBEE HIGBY